When Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary reached the top of Mt. Everest in 1953, crowds worldwide celebrated their success as a milestone for all time. While he was at the top, Tenzing set into the summit snows some gifts he’d carried up for the goddess who inhabits the peak, known of course to him and his people as Chomolungma. Few people paid notice to this, and far fewer understood the Sherpa and Tibetan identity behind this ancient name for the mountain.

This is the story of the same peak imagined as both Everest and Chomolungma, two identities that inhabit our imagination through two very different civilizations and two different visions for inhabiting the earth. Everest and Chomolungma are concepts living in our minds like estranged step-siblings in the same royal household, each operating in different wings in the palace. One is the exalted son, regal in his mathematically ordained mandate to reign as the rock-star king for all time, even as the kingdom goes awry. The other is his elder step-sister, beautiful and rock-solid wise with deep celestial powers but fairly dismissed, misconstrued and nearly overshadowed and exiled even from memory behind the glare shined on her younger brother, even as she works in obscurity to hold the realm together.

Mt. Everest’s crown was bestowed by the Royal Geographical Society in the 1850s, starting with long-distance telescopic triangulations from the Indian plains. Calculations revealed the peak’s supreme height, and as Britain’s lords of geography quietly took the time to triple-verify their find they saw the symbolic opportunity they could not resist, to stamp it with their claim. The Society had rules to prioritize native names, and of course they owned a premier storehouse of geographic knowledge, including a French-Jesuit atlas bearing the label (based on a Chinese source) Chomo Lancma. Nevertheless, in 1857 they overrode internal controversy and those rules and named the peak in honor of their emeritus Surveyor General George Everest (actually pronounced “Eve-rest” in his native Welsh) expressly to establish title before native names could become known. The long-distance titling was barely a footnote in the Society’s epic, multi-decade Great Trigonometric Survey to order the whole subcontinent of India into a grid for governance and taxation, but the Everest claim created the everlasting symbol to inspire humanity to bring the world, however far and high, into our comprehension and fold. By the time of the 1953 climb the very name had become our synonym for ultimate challenge, and the mountain became our monument to seeing our surroundings as the great, can-do field for the ascent of man.

To understand the identity of Chomolungma, we first need to appreciate that Tibetans and Sherpas revere mountains not by comparative height. Like most of the millions of Buddhists and Hindus from Lhasa to Mysore, they understand the most revered mountain on earth to be Kailas (Kang Rinpoché in Tibetan). Kailas is an unmistakable sight and a breathtaking presence reigning over the highest western highlands of the Tibetan plateau. Though its towering snowcap reaches to not even 7000 feet lower than Everest, a nexus of remarkable characteristics–including its location overseeing the sources of central Asia’s four major rivers–give it its identity as the earthly eminence of the Axis Mundi, the mythic spindle linking earth and the cosmos around which the world turns. For centuries people of many faiths have known Kailas as the world’s loftiest site for deities and mythic human tales, and countless people have made long, hard pilgrimages to circumambulate the peak and embed themselves in its affirmation that, regardless of how bad things seem, at Kailas the world is working wondrously and as it should. At least a couple of modern mountaineers have applied to be the first to climb it, but international outcries of sacrilege prompted China to deny those plans.

From their homes near Everest, Sherpas also revere a topographically modest “local mountain” called Khumbiyula. This rocky prominence is much more important to them than Chomolungma because it’s the home of a deity who oversees their privilege to inhabit the territory and the well-being of their fields, houses, forests, wildlife and rivers. As with Kailas no one is allowed to climb on Khumbiyula.

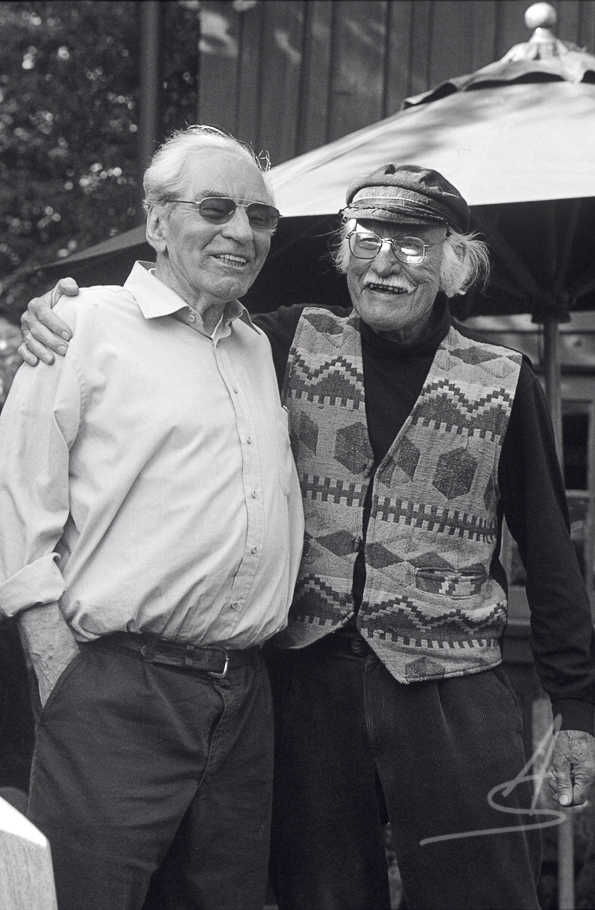

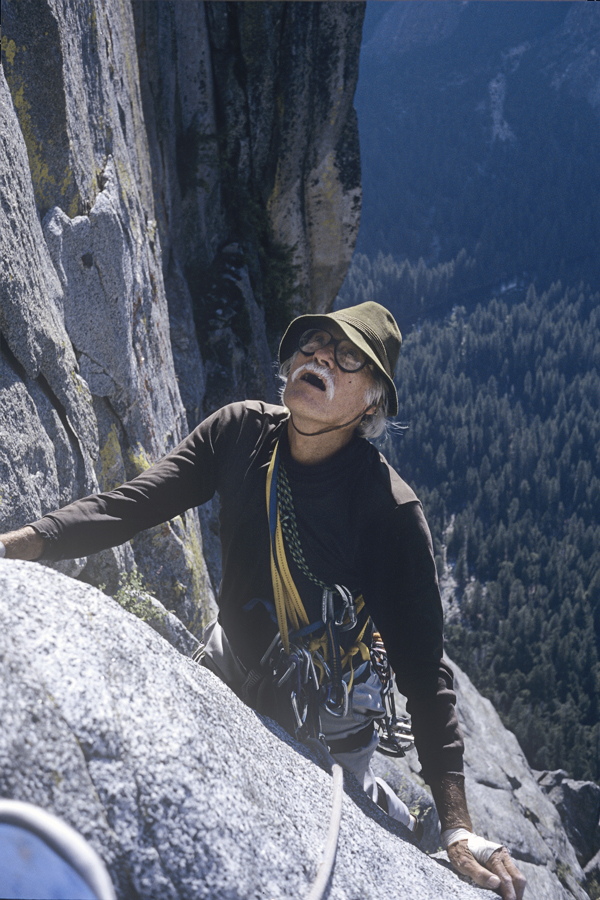

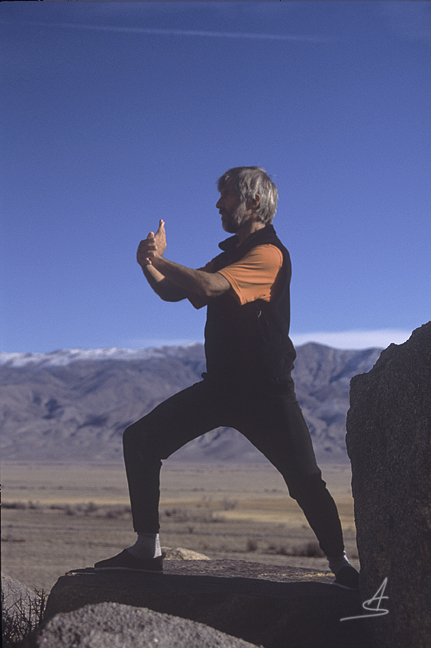

Since 1982, from Khumbu to Skardu, I’ve spent a lot of time with Himalayan natives; trekking and climbing with them, helping harvest their crops, raising money for their kids’ schooling, helping build solar heating, celebrating festivals, sitting in their kitchens listening to their stories…and the accumulated four years of life in their hospitality has opened my eyes as much and probably more than my Himalayan climbs and panoramas. I’ve seen seemingly desperately poor people glow with life in their simple villages and nomadic camps, telling how they love their basic foods and their animals, and how men and women collaborate to hand-spin and weave their clothes. I’ve also heard them chat about herding us foreigners, “like cattle–they give a lot of milk but need a lot of attention.” Instinctively they respect how their lives run both plentiful and dire, depend on the grace of their surroundings, and how peaks like Chomolungma oversee it all.

Before modern times Chomolungma was not well known across Tibet, and not always by that name. When Brits first applied to the office of the Dalai Lama to try to climb the peak in the 1920s, the officials in Lhasa issued travel documents labeling the peak with a complex name referencing its height as so great that no birds could fly over it. This was also how Tenzing said his mother referred to it. Folks living in sight of the peak also called it Cho Kola. Had the Brits applied to climb a more deeply sacred peak like Kailas they never would have received permission, and as it was they violated the rules of their permit by mapping Everest’s surroundings and killing birds and wildlife for biological study.

Today we know that the original, Tibetan name for the peak is actually Chomolangma. The British vanguard in Tibet learned the name Chomolungma from Sherpas hired in Darjeeling. They asked into the meaning, but people from different areas told them different things, the Brits interpreted those things differently, they projected assumptions of cosmic grandiosity into what they heard, and they came up with interpretations feverishly wrong. George Mallory and others published the fantasy that Chomolungma means “Mother Goddess of the World,” and eventually the world attached to that fable and never really looked into it. I’m guessing the Brits never got it right because they rarely sought out the local lamas. In Tibetan and Sherpa societies lamas carry the core religious and cultural traditions, and as a rule they don’t usually interact casually with general society.

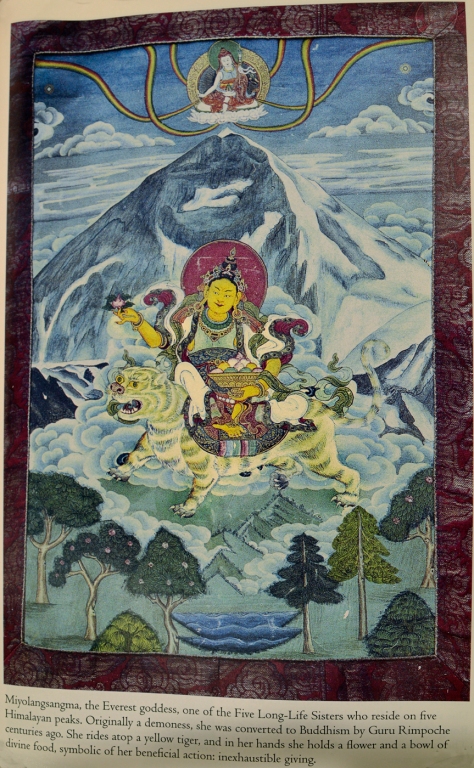

Researchers, authors and lamas today do explain the true definition of Chomolungma, and it starts with this: the peak itself is not a goddess, it’s the abode of a “local goddess.” Her name is Chomo Miyo Langsangma. This translates as “immutable elephant fair lady goddess.” Chomo is the term for goddess or revered female. The elephant (lang) reference is said to be an emphasis on Miyo Langsangma’s unshakeable (Mi-yo) resolve (in her role of giving generously), and the arched, grey back of her mountain. The abode, “Chomolangma” and the Sherpas’ derivation “Chomolungma,” are typical Tibetan contractions of her name.

Chomo Miyo Langsangma is one of five “local sister-deities” who can command certain local forces. Collectively they are known as the “long-life sisters,” each inhabiting different peaks. One sister leads the clan, and her name is Tseringma, Tibetan for “long-life.” Her abode is a magnificent, twin-peaked mountain west of Chomolungma also called Tseringma. (Hindus of the plains know this peak more famously as Gauri Shankar.) Each of the sisters has specific powers to help people live longer lives. Legend has it that it that centuries ago the sisters were visualized as capricious demons lurching people around with assistance and disasters rained from on high.

As told in The Lawudo Lama, Jamyang Wangmo’s highly regarded book portraying esoteric Buddhist traditions in Khumbu, Miyo Langsangma’s particular “long-life” power is to bestow beauty and wealth, especially successful crops and herds. She is depicted as a beautiful woman-figure boldly riding a lactating tigress, bearing in her left hand a bowl of delicious food, and in her right another symbol of proffered bounty, either a mongoose or a flower. Thus for centuries Chomolungma has stood as the home of a goddess supporting people’s prosperity. What’s fascinating to realize is that today Chomolungma brings prosperity in spades. Any Sherpa will tell you that they go to Everest for work; it’s risky but it’s the premier opportunity for glory and by far the best money in town. Thanks to Chomolungma, Khumbu Sherpas are the wealthiest natives in the Himalaya. This is a practical understanding that still respects the transcendent power and status of Miyo Langsangma. Tenzing, before he went to climb to the top of her abode, visited a lama to learn about the proper ways to respect the goddess, and he acquired a sacred thangka image of her for his home in Darjeeling.

As Buddhists, Tibetans and Sherpas appreciate that however virtuously we strive, even a prosperous, long and beautiful life finds suffering and troubles, and is temporary in any case. These are the Buddha’s teachings. It is said that Buddhism came to Tibet with a masterful tantric yogi, a “second Buddha” known as Guru Rinpoche, in the 8th century AD. Like a new sheriff soaring across the realm he confronted mountain deities like the Tseringma sisters and leveraged them into vows to help people by giving them earthly security sufficient to follow the Buddhist path and transcend material life. As Sherpas told scholar Jan Sacherer, “The mountain gods are for growing crops…but to purify our minds we need to pray to the Buddhist gods.” Tibetan cultures understand better than we that our definitions of mountains are projections of our imagination. Whether people believe in their gods literally or metaphorically, from a Buddhist standpoint it’s the quality and state of mind that the beliefs foster that makes the difference.

Guru Rinpoché also issued prophecies, and Sherpas believe they have lived out his foretelling that in hard times people would find hidden refuge lands called beyul. In the 16th century they fled from conflicts in eastern Tibet, and out west (Sherpa means “Easterner”) they explored south across high passes between the Tseringma peaks. In territory now in Nepal they found uninhabited and verdant mountain valleys with tumbling rivers and majestic forests, clearly beyul. On the precious and picturesque mountain slopes they made new homes and vowed not to harm wildlife or cut down whole trees, and to honor deities inhabiting the peaks. The Sherpas’ legacy is a typical if grand example of the cultural structures that inspire indigenous peoples to live with gratitude and respect for their terrain; they know their lives depend on it.

These then are the stories of Everest and Chomolungma. As the world’s most famous landmark, Mt. Everest is the alpha monument to our ascent-of-man vision for inhabiting the earth, and by that measure we’re doing well. We now ascend the once-unattainable peak regularly, and by the path of distilling the world into what we can define and succeed in we’ve advanced to the moon and so many ever-higher unimaginable heights. We’ve done well except that we look around and see the world we stand upon and depend on facing climatic, economic, political and biological crises wrought by the very hands we raise in triumph. No longer can we credibly believe that the ascent of man as we’re working it can achieve the mastery our forefathers expected. Rather, it’s more like we hope and pray that we are keeping ahead of colossal folly. Our situation feels like the lesson of uh-oh that every mountaineer learns–that summiting a great mountain is fantastic but our grand sense of completion faces the start of a vital and often perilous return to where we really live.

Chomolungma, the same mountain, is a huge emanation bearing the powers of the terrain around it. It’s a great peak that offers support to people who respect it, and it infuses people with a vision of our inherent vulnerability and dependence on our surroundings. I speak merely as an amateur observer of indigenous life, but I’ve seen in Ladakhis, Sherpas, Baltis and others a deep happiness and a respectful and active love for belonging to terrain that we with ever-mobile modern powers can barely imagine. Chomolungma focuses and enhances that vision of belonging and dependence on earth. We should not, however, confuse well-being and secure in belonging with ease and comfort, or even security in general. Indigenous living is full, difficult, and rich in hardship. Out of hopeful opportunity, dire need and heartbreaking fate Himalayan people are shifting away from their subsistence patterns. They are seeking better lives with at least one leg in the modern world while retaining their indigenous identities as best they can. In this year’s Sherpa celebrations in Khumbu for the anniversary of the 1953 ascent, I’m told that respect and rites for Chomo Miyo Langsangma were more prominent than ever. This is a sign of hope, it follows an instinct to bring the estranged step-siblings of Everest and Chomolungma together in the palace chambers of our mind. Whatever our current means, we would do well to blend in our minds both the will for Everest-inspired powers of proficiency and the indigenous respect for Chomolungma-inspired vulnerability. What other choice do we have?

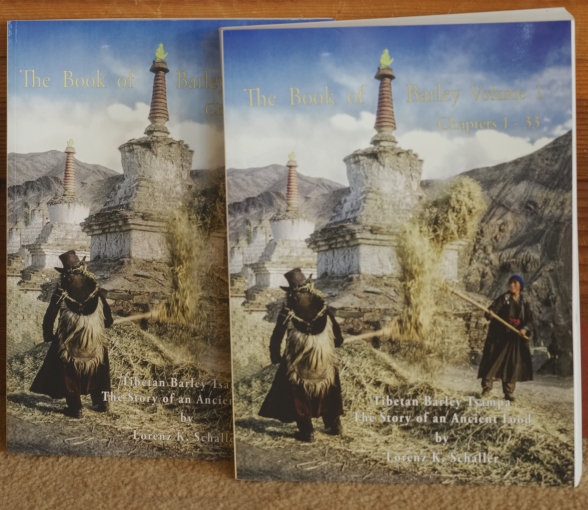

Information on Chomolungma and Chomo Miyo Langsangma in this article has come from many sources. I’d particularly like to thank Edwin Bernbaum, author of Sacred Mountains of the World, and Jan Sacherer and Barbara Brower, authorities on Sherpa and Tibetan culture. The latter two recruited helpful corrections and encouragement from Ani Jamyang Wangmo and Tashi Tsering. I’d also like to thank Losang Rabgey and her amala.